Introducing: The Reconfusion Workshop method

With this text, we will share a method that has come to be one of the main tools in our toolbox when solving complex strategic problems for clients. It aims to move the group from confusion and individual definitions to clarity and common understanding of a specific strategic problem, however big and multifaceted it might be.

The name of the method? It’s a play on the words “reframing” and “confusion” and is a reference to the phrase “confused on a totally new level”. We consider being confused on a new level to be a success, since the method claims to provide clarity on what the problem is, but not on what to do about it (that’s for succeeding experimentation). The phrase also implies that the confusion now resides on the group level and that the participants have the same confusion, not several individual confusions.

The situation

Let’s imagine an arbitrary management team facing a complex strategic challenge, like failing relevance and increasing competition. There’s a multitude of potential paths forward and depending on who we ask the obvious answer is different. To the marketing manager, it’s a matter of brand equity, to the product manager the problem is a failure to execute innovative ideas and to the CFO it might be a matter of cost-efficiency.

A classic rational approach to this situation would be to try and look for answers to reduce uncertainty, asking “how can we prove or disprove each and one of these claimed main problems?”. The choice of method might be to launch investigations, discussing, debating and arguing among peers, hiring consultants to provide recommendations or simply “putting your foot down” and just decide on one of the alternatives. After all, being assertive and quick to make decisions is a celebrated trait with leaders!

Our view is instead that travelling in complex and uncertain terrain is not about eliminating uncertainty. It’s about navigating it and learning from continuous exploration. More often than not we find that the answer on where to go and where to begin resides inherently in the group and the challenge is to explore all the perspectives on the problem, creating a common understanding and making conscious decisions on which perspectives to let guide the group.

What it is and what problem does it solve?

The Reconfusion method is a facilitated process, centred around one or more workshops, used by a group facing a complex strategic problem, to quickly achieve clarity and a common framing of the problem and induce action and progression into uncertain, unpredictable and complex terrain.

If done properly, the workshop should result in a reframing of the problem that:

- Provides clarity to the group about the problem, making it more focused but still nuanced

- Provides a strategic direction for the group, regarding the problem in question

- Is based on a common understanding within the group, of the problem and of the insights led to the reframing of the problem

- Induces action and progress into uncertain terrain, with the ambition to continuously provide more insight

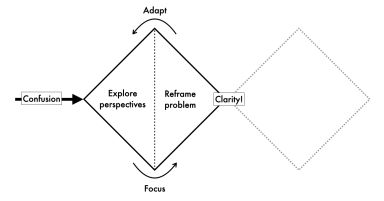

The foundation of the method is the principle of alternating divergent and convergent thinking. If you are familiar with the Double Diamond framework from the realm of Design Thinking you might want to think about the Reconfusion method as one way to iterate the first diamond, like this:

The Reconfusion method can be used to iterate the first diamond in the Double Diamond framework.

The workshop works well when:

- The problem or strategy is owned by a specific group, i.e. a management team, product team or a transformation steering group

- The group finds the problem confusing, with lots of “moving parts” and is having problems discussing it since it’s hard to know where to focus

- Necessary facts and knowledge to get started is inherently resident in the group

- Calendar time is of the essence and quick progress is desired

- Learning is a priority, meaning progress is needed in order to acquire more insight into the problem

In a nutshell, this is how it works. A group gathers in a workshop setting and with the help of a facilitator move through these five steps:

- Align on a high level. The group agrees on the problem to solve.

- Explore perspectives. The group uses divergent thinking to find as many ways as possible to see the problem.

- Find patterns and insights, using lenses. The group examines the different perspectives to see aspects of the problem they did not see before.

- Redefine problem. The group uses convergent thinking to make conscious decisions on what aspects of the problems matters most to start exploring.

- Sanity check! The group takes a step back and reviews the result before returning to reality to use it.

What’s different with this method?

There are other methods that solve this same problem. Some of them work fine, we even use a couple in our own work. You know, choosing the right tool for the purpose. We tend to gravitate towards this method for one main reason: it’s just simple enough!

When designing a method you have to balance between:

- Making it easy to understand, follow and perform consistently every time, but risking to simplify reality too much and therefore flattening complexity, and

- providing flexibility, sophistication and context-sensitivity, but making it more difficult to conduct and demanding expert facilitation and knowledge.

The Reconfusion method follows a pre-designed pattern but takes some skill and comfort to facilitate and needs tailored adjustments to context for each occasion. The result is nuanced, focused and sophisticated and also consistent and usable. Although being a defined and facilitated process, this method allows (and demands) for the intellectual presence of the members of the group. They are going to need to use their brains both inside and outside their comfort zone. The method is efficient, but we don’t claim for it to be easy or comfortable.

In a nutshell, what sets this method apart is that it embraces complexity and does not simplify to make the exercises comfortable, especially in the tricky but powerful step find patterns and insights using lenses. While some methods almost guarantee a usable result (“just trust the process and you will have something useful in the end”), the Reconfusion method can fail to produce a satisfying output because it forces the group to remain in complexity.

The setting

What you need:

- Confusion about a complex strategic problem

- A group that is invested in that problem and has the mandate to decide the strategic direction

- A meeting set up (physical or digital) with lots of shared visual space (whiteboard + sticky notes or digital equivalent). Ideally, you have access to sticky notes of four different colours.

- Time: between three to twelve hours (more on this later)

The group does not have to prepare in any way, in fact, it’s preferred if they are instructed not to prepare, just to show up and be prepared for the creative solving of the problem in question.

The description in this text assumes a physical setting with participants in the same room. You might just as well want to conduct this workshop in a digital setting. Just adjust the instructions for the tools and systems you have available.

How to do it!

Below is five steps that describe the method from start to finish.

1. Align on a high level

The first step of the workshop is to align on a high level and agree on the problem to solve. More often than not this is quite quickly done and does not need a more creative method than just asking the group, or even suggesting a predefined topic. Since the purpose of the workshop is to reframe the problem the exact wording of the problem is not that important, but the scoping is.

For example: if the CEO takes command and suggests “failing sales to new customers” as the problem and other members of the group has definitions that fall outside that scope, the scope should be increased to something more like “prevent failing relevance and profits” thus leaving it to the workshop to narrow it down from there.

Advice to the facilitators:

- Don’t be afraid to steer this part firmly

- Lean towards broad definitions rather than narrow ones at this point

- Don’t allow for too much debate on the exact wording

2. Explore perspectives

Now the fun begins! This part should take up roughly half the time of the entire workshop. The purpose of this step is to reveal and expose as many perspectives on the problem in question as possible. No perspectives are wrong or unnecessary, filtering will take place later.

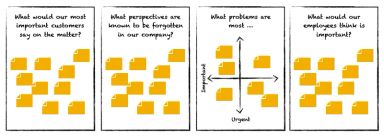

The general idea of this step: around the room is several boards or flipcharts, each with the headline of one perspective provider. A prospective provider is a rhetorical question designed to mine for perspectives on the problem. When the step is finished these boards are filled with notes containing individual perspectives.

Examples of perspective providers.

The design and number of perspective providers need to be contextually designed for each workshop. But here are a few ideas and advises:

- Consider questions from different ends of “dimensions” such as hierarchy or value chains, including for example employe vs. top management perspectives and customer vs. supplier perspectives

- Consider questions that mix structural, political, human or symbolic perspectives, including for example the corporate culture, current process, funding and currently hot topics in the organization.

- Your question doesn’t have to be one verbally phrased sentence, it can be a sense-making model such as a two-by-two, a coordinate system or a continuum.

- We recommend the number of perspective providers to no fewer than four and no more than eight.

The exact exercise in this step can vary, depending on the number of participants, number of prospective providers and the time available, but here is a suggestion:

1. The time available is divided with the number of perspective providers

2. The group is divided into pairs and the pairs are instructed to focus on (move to) one perspective provider per pair

3. For a small amount of time (1–3 minutes) everyone (quiet and individually) writes as many answers (perspectives) to the question as possible.

4. When the time is up, the pairs tell each other what they wrote and then try to come up with even more notes for a small period of time (2–5 minutes). The point here is not to comment on each other’s notes or choose among them, just to spark ideas for even more notes.

5. The pairs rotate to the next perspective provider and steps 2–4 is repeated until every pair has visited every perspective provide.

An alternative exercise is to simply allow for the group to move around, individually or in pairs, in the room and write answers (perspectives) to the questions as they appear in the discussion. This exercise tends to produce fewer perspectives.

Ideally, the two exercises are combined. After every pair have visited every perspective provider, the participants are allowed to move freely around the room to complement the now produced notes with even more notes.

Advice to the facilitators:

- You have succeeded in facilitating this step when participants are surprised by the sheer number of perspectives and that they had not imagined so many of them.

- Not enough perspectives? Expand this step. You’re better off with enough perspectives and too little time for the remaining steps than the other way around.

- Don’t be afraid to tweak the perspective providers if you find they don’t yield results. Producing many notes with perspectives is more important than the exercises being consistent for all participants.

- If engagement is slow, you might want to take a small time-out, and allow for a meta-discussion about the exercise and how to approach it. Some participants might not be used to exercises that allow for this amount of interpretation.

3. Find patterns and insights, using lenses

So, now you have a room (or a digital space) with lots of perspectives on the confusing complex problem. Hopefully, the participants harbour some level of surprise at this moment, as there are many perspectives they simply had not thought about.

Now the process of narrowing it down starts. But first. Make sure that you:

- Give everyone the chance to ingest all the perspectives (to the level of quickly reading through all the notes), regardless of what exercise you used in step 2.

- Take a break! If you’re doing a one-day Reconfusion workshop it’s ideal to hit this point by lunchtime.

At this point many workshop methods, even ones we use, would jump right into sorting, removing and prioritizing perspectives. But we’re going to stay in divergent mode and accept complexity for a bit longer. It’s time to try and see what we can learn from what we have in front of us, mining for patterns and insights.

The general idea of this step is to try and see patterns and insights that are not written ON the notes but resides between, as a result of several notes or even as a result of notes not written. When the step is concluded we have several new notes, preferably in a new colour, with patterns, insight, or questions to dig further into. You should allow roughly one-quarter of the total time for this step.

To find these patterns we need to introduce the concept of lenses. If perspective providers are rhetorical questions designed to produce perspectives, lenses are rhetorical questions used to produce insights from the available data (the data, in this case, is the total volume of perspectives).

To give an example from a non-related situation: when proofreading a text, the person doing it is reading the text with the lens “Is this part grammatically correct?” as opposed to when giving high-level feedback to the same text. Then the lens might be “Is this part interesting?”.

Below are a few examples of lenses that might be useful in the workshop.

Three powerful questions:

- “What does this mean?”

- “What can’t be solved?”

- “What is unknown here?”

Goals, resources and constraints (inspired by Six Simple Rules: How to Manage Complexity Without Getting Complicated, by Yves Morieux)

- “What goal is trying to be achieved here?”

- “What resources are used to achieve that goal?”

- “What constraint is stopping the goal from being achieved?”

Four frames (inspired by Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership, by Lee Bolman & Terrence E. Deal)

- Structural frame, Political frame, Human frame, Symbolic frame

- “What frame is dominant?”

- “What frame is missing?”

- “What does this frame mix imply?”

Miscellaneous lenses:

- “What is noteworthy? What pops out?”

- “What perspective is missing here, and why?”

- “What is just ‘typically’ us?”

- “What is surprising here?

- “What is confusing?”

- “What do I want to know more about?”

Here is a suggestion on an exercise for this step:

1. One part of the room, for example, one big whiteboard or one wall is reserved for this step, and divided into four portions: lenses, patterns, questions and one left empty for now.

2. The facilitator explains the concept of patterns and lenses briefly to the group. It is important to stress that a pattern does not have to be correct or true. At this point, it is work in progress!

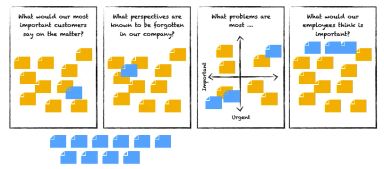

3. Every participant is equipped with notes of a new colour. If the perspective notes were yellow, the pattern notes might be blue.

4. The facilitator has chosen a few (3–5) lenses that should be useful in this case and has written them on the lenses portion of the mentioned wall/whiteboard.

Examples of lenses, written on the first fourth of the reserved wall.

5. Participants are asked to walk around the room, individually and silently, applying the lenses to the data (available perspectives) and as soon as a pattern appears, write it on a note and stick it anywhere (where it makes the most sense or where it happens to be most convenient, it does not matter). This is typically quite difficult and uncomfortable at the beginning. Most people are rarely asked to think this freely. Give it time.

Patterns, on blue notes, placed where they made most sense or was most convenient.

6. After a while, the participants are asked to pair up in couples and continue the same exercise but as a small team, discussing and helping each other out.

7. The exercise is done when to group is having trouble seeing more patterns or when time runs out.

Advice to the facilitator:

- You have succeeded in facilitating this exercise when the participants are surprised by what they came up whit. It is not uncommon that this exercise produces thoughts that have never been thought before.

- Facilitating this exercise can be challenging with some groups, especially groups keen on facts, statistics and correct answers. Set your expectations accordingly. Simple patterns as “this thing is mentioned in many of the perspectives” can be valuable enough in the next step

- When things are slow, don’t be afraid to interrupt the exercise to give explanations, take up questions about the exercise or throw in curve-balls. Maybe you should try another lens?

4. Reframe problem

At this point, we have visualised the multitude of perspectives on the problem and we have started drawing out patterns in the collective understanding of the problem. Now it is time to start making sense of the combined sum of information at hand.

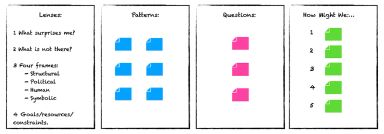

When this step is concluded, we should have produced:

- A selection of patterns the group found significant

- A selection of questions about perspectives or patterns the group found interesting but that was not clear enough to chose as significant. These questions are for further exploration.

- A reframed main problem, in the form a condensed number (2–5) of core challenges. We suggest using the “How Might We …?” format for these challenges as they provide a consistent forward-leaning instead of a problem leaning phrasing.

This step is a lot about grouping, reordering, categorizing, removing and prioritizing information. An experienced facilitator might have a thousand ideas and well-rehearsed ways to do this. Feel free to improvise and use those! What’s important here is to guide the group to collectively narrow down and make conscious and deliberate decisions together. The result should be as bought-in and collective as possible in order for the group to own the process ahead together.

Here is a suggestion on an exercise to reframe the original problem:

1. The facilitator explains the challenge ahead to the group: the difference between patterns and questions and the concept of HMW-questions.

2. Individually, the participants are asked to contemplate what patterns they found most interesting as guiding for the, individually and silently, for a few minutes.

3. Participants are paired up into couples and asked to discuss further what has struck them as most significant during the workshop so far. The couples are asked to condense what are the most important patterns, insights or perspectives and write them (or pick from already written notes) on notes in the pattern colour (blue in our case).

4. The couples are asked to present their candidates and place them in the “Patterns” portion of the wall reserved for presentations.

5. If a topic is considered interesting but has the challenge of being very unclear or in need fo more information, it is instead written on a note of a third colour and placed under questions.

The most significant patterns, and some questions on the wall reserved for results.

6. When the whole group has presented their most significant patterns and questions, all participants are asked to gather by the board. It is now the time for grouping, removing and prioritizing. Ideally, this is an organic and collaborative process with a moderate amount of facilitation needed. The facilitator explains the challenge as “agree on what is most important” and steps back. If the discussion gets heated, stuck or runs off in a strange direction the facilitator steps in to help. The result should be a few selected categories of significant patterns and a few selected important questions to explore further.

Chosen and prioritized patterns and questions.

7. Now it’s finally time to try to conclude the main challenges. The facilitator reminds the participants on the HMW-format. Then, much like we have been used to by now, the participants are asked to, individually and silently, write candidates for HMW-questions, on sticky notes (of a fourth colour). After a few minutes, participants are paired-up in couples to discuss, spark new ideas and write further candidates. The couples are then asked to present their suggestions on the HMW-portion of the reserved wall. These HMW-questions can be based on patterns, questions, perspectives or even be completely new. That is fine!

How Might We Questions, before prioritizing.

8. We’re getting close now. Let’s conclude our reframed strategic problem. The group is asked to gather by the board with the instruction to choose the most important HMW-questions. As with patterns, this should be a deliberate and collaborative process. The group is allowed to write new notes and make whatever changes they need, as long as they do it together. Ideally, the group agrees on a small number of HMW-questions. The hardest part is normally to prioritise and “kill darlings”. When a number of candidates have been grouped on the board, the prioritization process can be facilitated by a simple dot-voting exercise, where each participant gets a number (3?) of votes.

The result, including prioritized How Might We Questionss.

9. If all went well you now have a reframed strategic problem in the form of a few consciously selected main challenges and a few questions and patterns to provide depth. You are almost done! A short break to catch breath could be nice at this point.

Advice to the facilitator:

- You have succeeded this step if the group is “confused on a completely new level”. Often it is not just a matter of discussing, debating and compromising between the original perspectives of the participants. It’s about looking at the problem in new ways, and realizing there is a lot of common ground that was not initially realized.

- This step produces the final result of the workshop, and therefore is the most important. Sometimes it goes surprisingly smoothly as a result of the preceding steps. But if it doesn’t you do have to flex your facilitation muscles.

- If it seems impossible to achieve a satisfying result, a good idea might be to lower the level of ambition and pivot towards producing a result that focuses heavily on exploring and learning and iterate from there.

5. Sanity check!

Before ending the workshop and returning back to the reality of everyday work, a sanity check is in its’ place. The sanity check is a chance to review the result and control for any unwanted bias or results of accidental groupthink.

In its’ simplest form the sanity check is a group discussion about the result. How does it feel? Is everyone on board? What is exciting or worrying about the result? If done ambitiously some of the perspective providers from step 2 might work well as guiding questions for the discussion.

Here are a few suggestions on questions for the group to discuss:

- “What are your general feelings about the result?“

- “What was surprising about the result?“

- “What is very ‘typical us’ about the result? Is that a good thing or a mistake?“

- “What worries you about the result?“

- “What are you afraid we might have forgotten?“

- “What feels extra challenging?“

- “If we showed this result to top management/all employees/the board/the union/our customers/our partners, how would they react?“

There always is the possibility to make adjustments to the result at this point. But beware, this discussion is not immune to bias or premature conclusions. After all, the result is based on a quite thorough process. In these situations, we tend to advise, instead of doing more than just minor adjustments, trying the result out. Sleeping on it, giving it a few days of reflection and above all: doing some experiments and iterating it in practice. There is no such thing as perfect answers when dealing with complexity.

Now, congratulate your selves on reaching some clarity (or “confusion on a new level”) and common understanding on this complex strategic problem.

Adjusting the format to context

The Reconfusion workshop method is not a detailed guided step-by-step format, with zero preparations. That’s the point. As a facilitator, don’t do the mistake of thinking you can wing this workshop, preparing for half an hour in the morning the same day. The perspective providers and the lenses need to be thought through and you need to be mentally prepared for the discussions (or lack thereof) that will occur.

How much time do we need? We have done this type of workshops in durations altering from three hours to two whole days. There is no simple formula to know how long it will take. It depends on the complexity of the problem, the diversity of perspectives, the group itself and the facilitation. If you don’t have an idea either, try one full day, with three hours in the morning and three hours after a lunch break. It’s a reasonable middle ground.

Contribute to this method!

Have you tried this method and want to share the experience? We would love to hear about other peoples success, failure, adjustments or general experience. Just contact us and we will make sure to share new perspectives to the global community of complex problem solvers.

Anders Wengelin

CEO, Partner and Management Consultant