Diffusion—change as a social, not structural process

How to introduce new behaviours and practices organically in the organization.

In change management and large scale transformations, there is an underlying assumption that scale-up of practice and adoption of new behaviours is an individual process. When managers announce a transformation, the assumption goes that each employee individually reflects and decide if they should act or not, more or less in isolation. To put it simply, the change managers’ job is to make as many as possible to get on board, and if they succeed, they have won over “resistance to change”. For every person that has gone through the change process, they score and move on. One down, many more to go.

This mindset is so predominant that the whole notion of change management is based on it. Change managers have at their disposal various tools. They send individuals to training, update their processes and role description, provide them with new tools and methods and modify reporting structures. And they communicate. The reasons to change are obvious for anyone willing to see them. So it’s made in your face explicit and impossible to miss. And still, people ignore them and carry on with their work-life as if nothing had changed at all.

The inability to manage resistance to change is still at the top 3 of the reasons transformations fail according to managers’ surveys. Something needs updating, and it’s not a role or a new tool. Managers and change managers need to rethink the models for how change happens in organizations and what it means to lead change successfully.

Making it social

In a complex organizational setting, people never make big decisions in isolation. On the surface and in the conscious mind of the individual actions and decisions are rational, in the sense that they aspire to create the best possible outcome with what is known. But so many factors that affect decision making are unconscious. Peoples’ behaviours are highly contextual and heavily influenced by the people they interact with. Humans are susceptible to norms and social patterns, adapt to their context and copy other people’s behaviours.

For change management, strategy implementation and large scale transformations to reach higher success rates, change managers need to look beyond executing a structurally predefined set of activities that need to be checked off the list. Any change that affects peoples’ work needs to be seen as a social process that, in its essence, is based on interactions between humans.

Any change that affects peoples’ work needs to be seen as a social process that, in its essence, is based on interactions between humans.

Diffusion is a method and mindset for transformation and large-scale change in organizations. It differs from the classic roll-outs approach by recognising that change and transformations are a social process, not a structural one. Where classic change management is “push”, diffusion is “pull”, where classic change management is “roll-out of a new solution”, diffusion is “a movement of changed practices” and where classic change management is “making people comply to a new formal reality”, diffusion is “helping people work in new ways because it works for them”.

Diffusion itself is not the answer to “what works” to change practices and behaviour, for that we have Adoption. If you are not yet familiar with Adoption, please read the article Adoption — what change management was always meant to be. Adoption and Diffusion are both needed to making changes that stick and making what sticks spread.

Three factors need to be taken into account to make new behaviours and practices spread socially in the organization:

- The network, the infrastructure that enables the change to spread through the organization

- Change agents, the people ** ** that make spreading happen in the organization

- Virability, the inherent ability of the change to spread without the need for structural governance and management

The Network

According to the diffusion approach, change spreads organically through the organization when people adopt the new behaviour and expose them to others, offering them the alternative to adopt it. For new practices and behaviours to reproduce themselves to more people, people need to interact, and these interactions do not necessarily follow the organization’s formal and structural patterns.

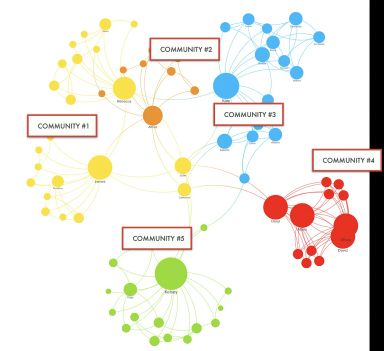

The (social) network visualizes connections between people in the organization and acts as infrastructure and enables the change to spread. It should not be confused with the organizational chart, which says very little about how to influence behaviours in the organization. In terms of diffusion and changing practices in a corporate setting, we want to map out the existing social network to determine what communities and clusters people belong to. Simply put, “who talks to who, who interacts to who and who listens to who?”.

Natural communities are often defined by the type of work or a shared identity (e.g. role, title, team, etc.). Still, any factor can play a part in forming the network, such as personal interest, numbers of years in the company or opinions on specific hot topics. Each of these “communities” usually has different aims and norms that an employee needs to adhere to for being accepted as a “member”.

The social perspective provides a more nuanced picture of how people are socially arranged in the organization and what it means from a change perspective. Managers driving the change initiative can use this information for deciding; where the change should start, what areas of the organization to avoid, who would be affected and how difficult the change would be.

How to get started

There are two common ways of starting to understand the network of your organization. First is to do a community analysis to paint a picture of the social network and its influence. The second and more easy one to start with is to follow the workflow. Since people regularly working together do have some kind of connection to each other and influence each other, it can reveal natural clusters and communities. Remember that whatever representation of the network you achieve to produce, it will never show the truth. Still, it can visualise valuable insights and paint a picture of the current network, that is useful.

Change agents

A change agent is a person that promotes the new practices and behaviours to others in the organization. It could be that they are part of the appointed change team, recruited for a specific task, or even that they are volunteers. They might not even be aware of their role as change agents, they might have simply adopted the new and started spreading it because it makes sense to them.

However, not all change agents are created equal. Some are better at starting the change, while others are better at spreading it through the organization by influencing, reinforcing and role modelling an ongoing initiative.

Let’s look at three archetypes of change agents and how they play a role in the diffusion of new practices and behaviours.

…not all change agents are created equal. Some are better at starting the change, while others are better at spreading it through the organization by influencing, reinforcing and role modelling an ongoing initiative.

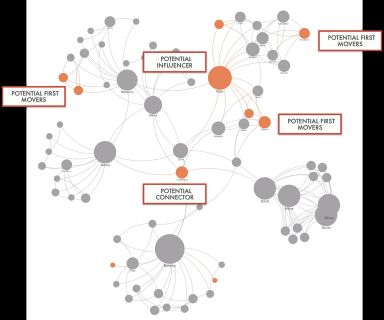

Role models or influencers are the people who occupy central positions in the organization. They are probably referred to as leaders, either of formal or of informal rank.

Role models are great at spreading information, reinforcing current norms and providing legitimacy. But, when it comes to more complex behaviours or behaviours that go against the grain of the organization, they are less suitable for leading the change.

The same social position that gives the leaders the ability to influence and spread information is a disadvantage for trying new things that go against the current norms. If they change the behaviour that got them their position, they risk damaging that same status. Most of these role models will not act for change until enough proof has been created for the change (they might nevertheless support it) and they are not suitable for being the ones that lead it.

Connectors are the people that act as a bridge of communication between two or more clusters of people. They are often found in the interface between organizational functions, for example, having one foot in business and one in tech or one foot in sales and one foot in product development. They are crucial for scaling your change by being trusted members of both communities and well attuned to the norms, problems, and barriers. However, just like the role models, they will most likely not lead the change since they have too much norm pressure to conform from both communities.

First movers are the people that might lead the change. They are usually less norm sensitive than their peers, a bit dissatisfied with the status quo and do not occupy central positions in the organization. You will most likely find them hidden away in some corner of the organization, where they are silently breaking the norms and making progress. Their invisibility is their most vital asset, and these are the people you want to engage at the start of the transformation.

Recognizing that different types of change agents should serve different purposes and thus finding tactics for recruiting them and working with them throughout the change, managers can increase the chances for successful diffusion of behaviours and practices dramatically.

How to get started

So how to find these different types of change agents? One way is to use a weighted social influence graph to determine where they are most likely to be in the organisation. For example, the first movers would probably have low exposure and medium influence. Another way is to make informed guesses. When hearing or reading an explanation of an archetype as the ones above, names and faces might pop up. Asking around, based on those archetypes, might be a good start. A not as good option would be to make internal advertisements for them since people’s perception of themselves tends to be skewed.

In cases where the ability to tailor the group of change agents is impaired, just going for diversity is a good idea. Including people from many formal and social contexts, roles, and experiences in the organization increase the chance to check several types of change agents, which is not a bad thing. Just start working and pay attention to how the change agents approach the task of diffusion and how they perform and adjust your expectations and how you help them succeed.

Virability

People copy each other, consciously or subconsciously. We would probably not survive as species if we didn’t have the ability to mimic what other people like us do. It’s essential for informing proper behaviours in our communities and selecting better solutions. When we lived in caves, maybe it was all about what mushrooms to eat and snakes to avoid. In modern time it’s more about how many rolls of toilet paper to hoard when a pandemic breaks out or what to say to avoid unwanted looks during a presentation round in a big meeting. When simple behaviours are copied, they are visible right away. From one day to another more people have started doing things in that new and improved way. But more complex behaviours are much harder to observe when they are adopted and spread. They are often broken down into smaller components that are adopted over some time with small adjustments.

Virability is about how easy and desirable the behaviour or practice is to copy. In an organizational setting, three reasons are common for people to copy and mimic each other; copy if better, copy the majority and random copy.

Employees apply the “Copy if better” mechanism when a new practice or solution is a noticeable improvement to current ways of working. In that case, the person’s identity matters less, and copying is directed towards the behaviour rather than an individual. Imagine someone found a better route to the cafeteria. Instead of taking a walk three flights of stairs, there is an elevator down the corner that is mostly vacant.

“Copy the majority” is applied when employees deal with conformity to the group or community based on a shared identity. In this case, people tend to adhere to what the majority does and copy if other people or groups are already doing the behaviour. The critical distinction is that this mechanism is based mostly on identifying with other people that are similar to oneself. “Project managers like me work in a new way, maybe I should too?”.

The last mechanism is about how employees deal with an overload with information that tries to influence their behaviour. When they simply don’t care, or don’t have enough time to figure out a new practice, they would benefit them or don’t know what the majority is doing. In these, not very uncommon cases, decision making tends to default towards “random coping”, just making any change or the first change that appears feasible and going with it.

Understanding these mechanisms is very useful when helping people adopt and spread new behaviours and practices organically. Appropriately leveraged, diffusion is faster and has a higher chance of success than traditional roll-out approaches. With these insights, solutions can be designed with adoption and diffusion in mind and make it less likely to avoid scenarios with random copy due to confusion and information overload.

How to get started?

First of all, the solution in mind needs the condition for adoption in its intended context. For a good chance of adoption, the new practice needs to consider problem/solution fit, identity and barriers (see the article on adoption, linked above). Secondly, for diffusion to take place, it needs a strong start, in a limited context. This principle can be compared to the task of starting a fire. Out of many small sparks in a large area, one or two might catch fire, but if efforts are concentrated to one point, and flames catch on there, spreading them is just a matter of exposing more of the material to the fire. Thirdly, to avoid people doing nothing nor random copy, there needs to be enough difference between the choices they need to make, making it easy to understand what change means and how to do it. Be clear and differentiate amongst everything else they have to do. Lastly, when diffusion has started, the responsibility of the change initiative is to make sure “more material is exposed to the flames”, connecting people from different contexts, helping those who have adopted to introduce others to the new practices and making it easy to understand and join the movement.

Should you try the diffusion approach?

Before committing to an approach for driving change and transforming an organization, any change team should ask themselves “What matters most?” and “what defines success?”.

Does success equal quick progress and checking off well-performed activities? Will you destroy your career for not producing merely symbolic and directly measurable results, even though behaviours haven’t changed at all? Then the traditional approach is the best way to go. Make a pilot, roll it out and hope for the best!

However, if changing what people do and how they do it matters more, a combination of Adoption and Diffusion promises better chances for success. They don’t promise quick progress in activities and “number of people affected by the change”, but they accept change as the complex and uncertain forces they are.

Vadim Feldman

Founder and Management Consultant